The use of the term “decimation” reveals something of the barometric pressure placed upon a society to employ polysyllabic words without once reflecting on them. “Decimation” has become synonymous with “annihilation,” the removal of something from existence, literally “to nothing” and “obliteration” which is rooted in a removal from memory, collective or otherwise. “Decimation” is literally a “ten-ing” or “tenth-ing” from the Latin number “decem” meaning “ten.”

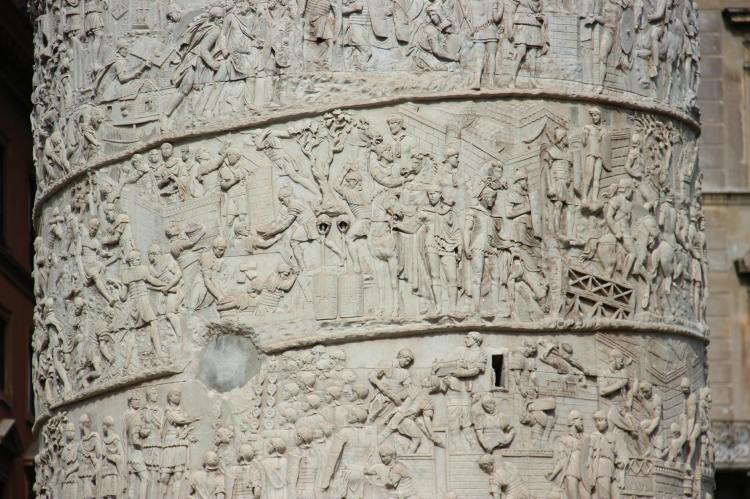

As an ancient Roman practice, decimation was the penalty levied against military units for cowardice in battle. Lots would be drawn at a ratio of 9:1 and the losing “tenth” faction would be beaten to death by their own brothers-in-arms. While our purpose here is not to analyze or otherwise judge the effectiveness of this practice in restoring morale or even begin to assess the psychological trauma for those surviving, it is important for our present inquiry to recognize that decimation did not entail nor intend the destruction of its object. The loss of one tenth, though severe, was not considered an insurmountable deficit to remedy deficient courage.

For all its faults, the discipline of Roman military decimation is, nevertheless, a pagan echo of the tithe due to God, an act of faith in the Father’s fruition rather than the ferocity of ferrum. While Abel gave the first fruits of his flocks, it was Abram, later Abraham, who first offers a tenth of his spoils from battle and the earth’s bounty to the priest of God Most High and King of Salem, Melchizedek (cf. Gen. 14:20). Before Moriah with “the fire and the knife” (Gen 22:6), Abraham offered a tenth of his spoils and harvest, trusting in the Lord’s main clause to Adam, “you shall eat,” despite the perspired condition of his brow (Gen 3.19).

Perhaps this piety of tenths played a part in the mind of J. R. R. Tolkien at the bridge of Khazad-dûm in another Moria (cf. Season 2, Episode 11, “Altum”) when the grey servant of the secret fire cuts off the passage to all pursuers and costs the fellowship a ninth of its number, a tenth if we do not discount the pity of Bilbo. Piety and pity are not mere sentiments but dignum et justum. In the mid-20th Century, Jacques Maritain developed the principles behind the United Nation’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and Dignitatis Humanae, the Second Vatican Council’s Declaration on Religious Freedom (1965). The success and, one might add, truth, of these documents hinges on the grounding of human dignity, not in the normative recognition of the common humanity of individuals and peoples, but the fundamental recognition by God which pre-exists and endures beyond all human recognition. Dignity is not so much a popularity contest and as it is exclusively an authority contest, for it is the author of all beings, who affirms all contested dignity on the Last Day to the rise and fall of many (cf. Luke 2:34)

Dignity at its core is a certain pointing with a “digitus,” from Latin meaning, “finger (or thumb).” Distinct from the Greek ἄνθρωπος (cf. Season 1, Episode 4, “Anthropos”), the Latin word for human being “homo, hominis,” possibly comes to us from the Greek ὁμός, meaning “the same” or “common,” reverberating philologically the remark of Adam to the embodied rational creature fashioned from his rib, who was unlike any other creature that God had made, “bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh” (Gen 2:23) and, we might add, knower of language.

The greater part of “love thy neighbor” is simply identifying the common dignity, pointing with one finger, declaring, “this is my brother or sister,” and defending him or her with all ten curled into firsts against all comers, knowing full well that if your fists and composite fingers shall fail and those of all other men, likewise, fall away, Our Father in Heaven still affirms, indeed, underwrites our indelible human dignity. This is not to conclude that humans are unable to act in ways contrary to their dignity. A certain translational mischief was spread across the anglophonic world through the translation of Genesis 1:27: “So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him…” (RSVCE). The mischief is the false impression that our current created state is the perfection or end state of our creation. The Latin of the Biblia Vulgata, which informed St. Thomas Aquinas’s thought, puts the “imago Dei” in the accusative case after the preposition “ad,” rendered, “ad imaginem Dei” or “to the image of God,” presuming movement in either the locomotive or metaphysical sense. Similarly, the Greek Septuagint renders the “εἰκών θεοῦ” instead with the preposition “κατά” meaning “down from” or “according to,” thus “κατ᾽ εἰκόνα θεοῦ,” meaning “from the image of God,” and in this way signifies creation flowing from the image of God, again, as a distinct and necessarily imperfect reality.

Therefore, being created “in the image of God,” “to the image of God,” and “from the image of God,” similar to our baptismal character is neither immutable immunity from the Eternal Law nor license to become anything less than a saint, a holy one of God, fit and fitted in dignity for the wedding feast of Christ and His Bride, the Church, from whom tithing and decimation have been woven into her founding and flourishing.

Although Frodo Baggins loses a tenth of his digits at the end of all things, a wound which never quite heals, our Lord and Savior lost a tenth of his disciples over Good Friday—Judas entirely by his betrayal and Peter by his denial through the three watches of the night versus the twelve hours of the day or one-fifth of Good Friday. Although His five wounds remain, His Twelve are restored to our Easter Joy and Pentecostal ardor.

Furthermore, the humble tithes, the one-tenth sacrifices, of countless Christians, yet countable and accounted by God, has not fettered the faithful into shuddering subservience. It has fostered courage at kitchen tables across time and continents as endless bills surpass the means to pay them. It should be noted once again, that tithing, the tenth due to God, is offered to Him freely for our good and bounteous benefit. When other agents such as the modern state and private usurers demand more than this divine limit, it offends our dignity by that injustice which is injury. “Courage” is a certain possession of heart, from the French “coeur,” and yet it arises in Christians, oddly through a certain rendering of heart, one’s core to God. As the Prince and princes of this world desire and enforce to take beyond this limit established by God and so woven into the story of our redemption, we may very well see in our own days the rendering to Caesar become the rending of.

Support BetterPears Through

BetterPears Leaves

Click Here to learn more

Be the first to know when the next episode of The BetterPears Podcast arrives!