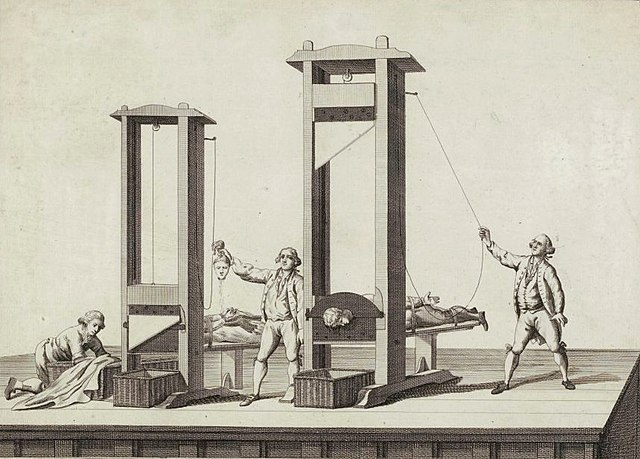

Certain words bear with them historical scars apart from their direct or even abstracted meaning promoted by Big Lexi, the lexicography cartel. When the equally true friend and good writer Charlotte predicates “Terrific” upon her porcine pal, there is, for some, a brief cognitive flicker of the French experiment begun in 1789, of la Terreur and the Committee of Public Safety. Perhaps the association is not unfounded in E. B. White’s tale as the spring pig so matured toward Thanksgiving dinner.

Another such scarred word is “immolation,” which conjures up the enflamed protests of Buddhist monks against the wars and military occupations of the last century or more recent protests performed by those spiritually engulfed by the burdens of an increasingly unjust world. Fire, however, is not the fundamental meaning of immolation. At its root is the Latin “mol” as in the noun “mola, molae, f.” meaning both “millstone” and its product, “ground grain.”

The connection with sacrifice and, indeed, burnt sacrifice in the ancient, pagan world is that sacrificial animals supposedly required consent to being offered to an equally supposed divine patron. The sign of consent was the lowering of the animal’s head, which was almost assured by the sprinkling of salted grain or mola salsa before its head. After consenting in this way, its throat would be cut and the body burnt in part or entirely as a holocaust, the latter literally a “burning of the whole.” In some cases, cereal or grain was itself the offering to be burnt. In both animal sacrifice and grain offerings, the aspect of sacrifice focuses on the loss of natural and proper goods as an atonement for previous transgressions or a display of dependence on the divine beyond the natural dependence we have for such possessions.

This is the phenomenon of sacrifice in natural anthropology. Sacrifice in this manner manifests our desire to turn back from the behaviors that are not conducive to our flourishing as individuals and societies. Sacrifice so viewed focused on the consuming fire; however, the destruction of the offering by whatever means is not the fundamental meaning of “sacrifice” from the Latin “sacer” and “facere,” that is, “to make holy or sacred.”

Holiness hinges on the distinction of the sacred and the profane. Profanity is today, perhaps, too charged a word for it is rooted in the Greek “φαινώ” meaning simply “to appear, be made visible.” It is the same root animating the word “phenomenon.” The pejorative sense of profanity is the making visible or common that which should be private and reserved. Hence the first aspect of the sacred or holy is the manner in which something sacred is set apart, concealed in its reservation.

Further, that which is common and profane admits of common use, such as a barber’s basin doubling as a hat or helm. Whatever is sacred, be it an object, a person, a place, or even a period of time, such a sacred thing is set apart for a definite purpose to the exclusion of others. The ciborium could hold breakfast cereal equally well but to its profanation and denial of its sacred purpose. The Sabbath’s hours may be sold as labor instead of offered as leisure.

The sacral dimension of ourselves and our world is an intentionally created weight and purpose informed within our soul. Much can and has been analyzed concerning destructive sacrifice, the great practice of our ancestors in futile mediation until the advent of Christ and His perfect sacrifice. While including the destruction of the temple, His Body, the totality of His sacrificial and salvific work did not end until its rebuilding, His Resurrection (see John 2:19–22). It is through participation in His Sacrifice through the sacraments and their informing of the Christian life that His disciples become the “living sacrifices” of Romans 12:1, and are increasingly made holy in this life and the next.

In this perdurance of the Christian pilgrim and not in the definitive, self-destructive act does the term immolation offer its truest meaning. Again, the Latin “mola” means both “millstone” and “grain,” which is related to the additional noun form of the same root, “moles, molis, f.” meaning “shapeless mass, pile, or load.” Both a millstone and its accumulated product, such as 6.02 x 1023 grains of flour, present us with the idea of a burden which can be overwhelming. Consider the millstone in Matthew 18:6, “If anyone causes one of these little ones—those who believe in me—to stumble, it would be better for them to have a large millstone hung around their neck and to be drowned in the depths of the sea.” In this particular example from the mouth of Christ, notice how the scandal of the young leads not only to the punishment of the corrupter but the loss of the community’s millstone, further burdening those seeking to be nourished and set aright.

If not entirely overwhelming, however, the burden of life and, here, the burden of the Christian life, of taking up our cross daily, has both a mollifying and a molitizing effect. The first such effect is from the Latin adjective “mollis, molle,” meaning soft, gentle, related to “mola” in the way that flour like a fine sand is softer to the touch than unmilled whole grains. In a more abstracted sense, “mollis” also means “effeminate.” While this latter sense must be viewed through the lens of our becoming the Bride of Christ and receiving entirely all that Christ desires for our good, the general sense of soft and gentle more clearly affirms the humble Christian, be he low to the ground —“remember you are dust”— or, simply by extended meaning, not proud.

Molitization (yes that is a neologism of a sort) comes to us from the fourth conjugation deponent verb “molior, moliri, molitus,” meaning “to make exertion, strive, or toil.” Such is the Christian’s response to the weight of the fallen world which he has been invited to renew, countering both the soft and hard bigotry against the faith.

In softening our wills to the will of Christ and in steeling our resolve in the face of oppression, Christian immolation as such self-sacrifice is neither the disciplined, Buddhist nihilism denying the good of this world nor the manic passions given to despair over an increasingly fallen world. No, the Christian witness, the Christian martyr, burns radiant with the love and surety of Christ veiled under the visage of milled wheat and crushed grape and is not in the end himself extinguished as in the holocaust of some mere ox or some pig.

BetterPears Market Mug Giveaway

Click Here to learn more

Be the first to know when the next episode of The BetterPears Podcast arrives!