There was a time, not so long ago, when the term “vaccination” was not on the short list of contentious matters which would get a social media influencer “cancelled.” While I hope to eschew the designation “influencer” for as long as possible and do not ascribe to give medical advice, —I am not that kind of doctor—the topic for this episode will nevertheless be vaccination.

The term has as its origin an observation by Dr. Edward Jenner who in 1796 noticed that people infected with the rather mild cowpox were immune to the more severe and potentially deadly smallpox. After exposing a patient to cowpox and allowing symptoms to subside after a few days, the patient proved resistant to subsequent exposures to smallpox. This process of inoculation was termed “vaccination” after the Latin word “vacca” meaning “cow.” “Vaccination,” by extension, is a certain “cow-likening” giving rise to terms such as “herd immunity.”

The biological function for conventional vaccination is rooted in the introduction of dead, mild, or otherwise weakened cells of a disease. The auto-immune system of the receiving human host is triggered by these “straw man” pathogens and develops corresponding anti-bodies to combat the pathogen when encountered in its healthy, virulent form. The whole process resembles the gathering of military intelligence to minimize the effect of a future attack.

Beyond the military, the Church, and here I refer to the Catholic Church on account of its historical perdurance and magisterial structure, the Church allows sinners into her midst. Being a sinner is the closest thing we have to a pre-requisite for membership with the exceptions of Jesus, Mary, and the angels. These sinners often have errant and destructive views of the faith, and yet the Church throughout every century has responded to these errors and those who held them with an aim to healing both the Church as the united Body of Christ and the individual. Of relevance here is the reality that doctrinal statements often follow in the wake of the errors and heresies that they address, much like the body responds to the pathogenic material in a vaccination.

Thus, the rhythm of conventional vaccinations seems to resonate in the body with the similar social response to ideological pathogens, that is, introduction, identification, response, and restoration. More novel vaccination methods now in common use seem to subvert this rhythm of our auto-immune system and modify the ribonucleic acid (RNA) or proteins structures that order all our bodily cells and their operations.

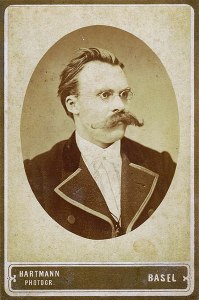

The whole situation seems to be a physiological playing out of what Friedrich Nietzsche describes in his Vom Nutzen und Nachteil der Historie für das Leben sometimes translated as The Use and Abuse of History for Life. The philosophic work is modern in two senses. It takes man as the measure of all things instead of God, and it is short and to the point, readymade for mass consumption.

In his Use and Abuse, Nietzsche introduces the unhistorical man, sometimes called the “Last Man.” The description given is in comparison to the grazing cow which fills its belly looking down at a truncated horizon of history. The unhistorical man’s concern is the satiation of his belly and the avoidance of pain, in which we can discern the recent mantra of our age, “Safety First.” As a foil to the Last Man are the historical man and the superhistorical man. The distinction is somewhat unclear in Nietzsche’s writing as he lists three approaches to history: monumental, antiquarian, and critical. The last approach, critical history, however, seems more aligned with what he describes as superhistorical and the person engaging in critical history, what he will refer to in a later work as the Ubermensch or Superman.

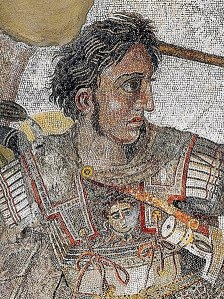

As for the two historical approaches, monumental and antiquarian, Nietzsche offers some significant nuance. Monumental history focuses on the great deeds of the past with a hope of a return to that past greatness. Monumental history is limited by analysis paralysis. Life and action, for Nietzsche, requires a suspension of history to live in the unhistorical or superhistorical now. For example, one does not become Alexander the Great by thinking too much about becoming great. Indeed, it appears Alexander’s greatest military victory displays a certain disregard for his personal safety, and his success as a conqueror was completely void of a succession plan as if his eventual death was never considered.

Alternatively, antiquarian history for Nietzsche is less selective of the high points of the past and seeks to take in a wider view of the past than simply the high points or monuments. The danger to life, according Nietzsche’s understanding of life, is that the antiquarian has too much reverence for the past and no discerning taste of what was best or even comparatively better. Our modern example would be moral or cultural relativism holding that all past principles and customs are of equal merit and worth.

In earlier times, these two kinds of historical men informed the unhistorical, unreflective Last Man with purpose, exemplars, and the virtues of self-denial or at least delayed gratification. What tends to replace these historical approaches in Nietzsche’s paradigm is the critical historian who wields both a destructive and constructive nihilism before the unhistorical man. Although translated for our audience, the root “crit-” in “critical” is derived from the Greek adjective “κράτος” meaning “might” or “strength” and accurately denotes the nihilistic will to power of this superhistorical approach. This nihilism is certainly destructive, as one could expect, extirpating ancient mores and principles recalled by monumental and antiquarian history alike. It is also constructive and creative in the strong sense, the sense in which the creating creature both blasphemes and negates the blasphemy by negating God. From the rubble of the fallen world, the Nietzschean Superman wills into being his own order and age, but he does so dispassionately, a martyr in his own eyes to an enduring cause of his own will projected upon the herd of unhistorical men, who are still chewing cud—their bread and circuses, no matter if ancient or modern.

Like his Superman, Nietzsche seems dispassionate as well in his exposition of these historical approaches. Although he sees critical history as most able to harness life through the will to power, he finds no need to democratize, that is, universalize it or even defend it. Critical history simply is the case of the world so far as critical history is able to reshape the world.

A reflective pause is necessary. In a world or rather a view of the world that eclipses God, the landscape grows cold and dark quickly. Our visceral response, as participants in what we consider a liberal democracy, is to strike out against the Superman: the tyrant, the demagogues, the oligarchs, who spell the word “FEW” backwards. Even if successful, this Superman will be replaced after a time.

The harder response, the response that voids the power of critical history, is the humble history that inquires into the past not as its master but as its ward and successor. The rejection of the critical history of nihilism in our market squares and mental horizons is not to topple the Superman but to cease to become the Last Man, the cow living in the now and for the now without history or intending future greatness. Regardless of the convalescence or malevolence to the body of conventional or modern vaccinations, this ideological vaccination against history and its genuine fruition breeds death to the human soul.

Be the first to know when the next episode of The BetterPears Podcast arrives!