The folks at Merriam-Webster represent the North American branch of Big Lexi, our philological archvillain for this season of The BetterPears Podcast. Their entry for the term “egregious” offers the contemporary definition: “Conspicuous, especially conspicuously bad.” The entry also includes an archaic meaning, “distinguished,” and an explanatory note that perhaps the shift in meaning from a compliment to something more accusatory is the result of the ironic use of the original meaning. “That is all there is to see here, people. Just a word that now means its opposite, a word to be added to the likes of ‘cleave,’ ‘inflammable,’ and the ‘bi-’ prefix in words like ‘bi-weekly’ or ‘bi-annual.’

As you might have guessed, I believe that there might be something more to this word which reflects our own understanding of its deep etymology and perceptions of belonging to or resisting the herds or flocks. “Egregious” comes to us from the Latin adjective “egregius, egregia, egregium.” The adjective is composed of two parts, the prefix “e” or “ex” meaning “from” or “out of” and the root noun “grex, gregis,” meaning “flock” usually in the context of sheep but in some contexts it can mean a more general “herd.” It is important to distinguish “egregius” from “extra-gregius,” namely that “egregius” means “from” or “out of the flock” and not “from outside the flock.” The noun, usually a person, modified by “egregius” has an origin from within the flock not somewhere or some flock exterior to it. Those egregious individuals might be a “rara avis” or “rare bird” but are nonetheless birds hatched from within the community itself.

The “e” of “egregious” confers, then, a meaning similar to the “e” in the word “election.” Those elected to offices (see Community: Episode 6) are selected, that is “se” + “lectus” from the community’s members. Pope Francis’s papal motto is “miserando atque eligendo,” a phrase taken from a homily of St. Bede in reference to St. Matthew’s call to follow Jesus. “Eligendo,” St. Matthew is called out, chosen from the milieu of his time and “wretched” circumstances to follow the Good Shepherd. The egregious are drawn out of, literally, distinguished from, the flock.

Returning, then, to focus our attention on the nature of flocks, in particular, flocks of sheep. The literal aggregation of sheep retains some of the advantages of a fleet as described in Episode 2 of this season on Classical Education. The flock is able to travel faster with each sheep not having to swivel its head in a constant search for predators. Each sheep attends to his visible range and sounds the alarm if anything seems amiss. This convention is taught to the young by the old. The difference between a flock and a fleet arises when the enemy does indeed appear. Absent a shepherd, a sheep’s defense, aside from perhaps a pair of horns, is his relative fitness to his kin. A fleet’s strength is the coordinated strategy and tactics of the ships in unison against the threat. Of course, humans man ships. Sheep have yet to become a seafaring species, and so if they ever do construct boats on their own initiative, I suspect their response to a wolf helmed vessel at sea will be similar to their slaughter of proverbial fame on terra firma.

In our historical imagination there must have been some providence to the survival of sheep in the world prior to their domestication by humans given the tastiness of mutton and a sheep’s lack of any significant defense. While flocks of sheep might have been a natural phenomenon, it is the human shepherd who orders and preserves them from wars, famine, and pestilence over the millennia, nevertheless for the sake of humans during wars, famine and pestilence over the millennia. Still this idyllic image of an episcopal shepherd over his sheep presents the tension in the modern interpretation of the word “egregious.” Namely, why was being described as “out of” or “from the flock” a positive description in the ancient world when it seems that what exists outside of the flock is danger and death?

Again we stand at the abyss of “deep etymology” and conjecture causes to explain effects. The fruit of this exercise is not certainty or even certitude but the habitus, the ready disposition, to ponder the weight of words which connect us to the human family over time and space.

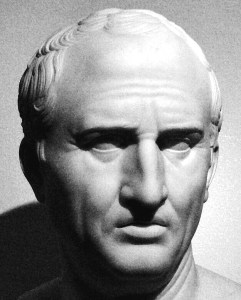

Perhaps the ancients saw the egregious sheep as the prime selection fit for sacrifice or the prime selection for the purpose of breeding the next generation. While today we might seek out the latest tech stock, back then the newest development in livestock was a societal premium. Transferring the epithet to humans, a novus homo or new man to the Roman Senate such as Cicero, would have been seen as a sanguine shock to the ebbing bloodlines of the consular class preceding him.

That is one theory for the ancient meaning of “egregious,” but what of the modern sense in which the term is now negative in connotation? Here there is perhaps a decoupling in the transference of the epithet. Human societies, unlike flocks of sheep, become complacent and resist changes to the status quo with intention and sometimes violence. Egregious members of a human society are seen as agents of change and there is a resistance to the change which is transposed as resistance to the individual. Such is the nature of revolutionaries and revolutions.

In the Christian revolution, that is the revolution initiated by Jesus Christ, which in the grand schema of the human family was something of a counter-revolution restoring the rightful king, we have the image, even from the first century, of Christ the Good Shepherd. We are told that His sheep hear His voice and follow Him, presumably leaving their flock. Which then is the true flock, the flock of origin or election? Does the narrow path of these egregious sheep necessitate egregious activity in the same aspect of our own Christian journey today?

This drawing out of flocks seems to be God’s modus operandi for the salvation of the human family. To His chosen people whom He exiled from their promised land for engaging in polytheistic worship contrary to His revelation as One, God reveals Himself as a Trinity of Persons. To creatures imbued with the natural law to care for the young and for the young to obey their parents, Jesus comes bearing a sword commanding His followers to deny their families, let the dead bury the dead, and come follow Him. Egregious behavior indeed.

So what thoughts came to mind concerning the episode?